Patricia Bath

Dr. Patricia Bath, ophthalmologic surgeon, inventor, and activist for patients’ rights, was born in Harlem, New York on November 4, 1942 to Rupert Bath, an educated and well-traveled merchant seaman, and Gladys Bath, a homemaker and housecleaner. They were loving and supportive parents who encouraged their children to focus on education and believe in their dreams and ideas.

Bath developed a love of books, travel, and science. She excelled at school and began to show her aptitude in biology in high school, where she became editor of the Charles Evans Hughes High School’s science paper and won numerous science awards. In fact, she was chosen in 1959 at the age of 16 to participate in a summer program offered by the National Science Foundation at Yeshiva University. She gained notoriety when, while working at Yeshiva, she derived a mathematical equation for predicting cancer cell growth. One of her mentors in the program, Dr. Robert O. Bernard, incorporated her findings into a paper he presented at an international conference held in Washington, D.C. in 1960.

Following this experience, Bath won a 1960 Merit Award from Mademoiselle magazine, completed high school in just two and a half years, and entered New York’s Hunter College to study chemistry and physics. She earned a BA from Hunter College in 1964 and then went to medical school at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

Bath finished her MD in 1968 and returned to New York as an intern at Harlem Hospital, followed by a fellowship in ophthalmology at Columbia University from 1969 to 1970. During this time, Bath began to notice differences among the patient populations in the hospitals where she had worked.

At Harlem Hospital, where there were many African American patients, nearly half were blind or visually impaired. But at Columbia Eye Clinic, the blindness rate was markedly lower. She conducted a study documenting her observation that blindness among African Americans was nearly double the rate of blindness among whites. She concluded that this was largely due to many African Americans’ lack of access to ophthalmic care. With this finding Bath established a new discipline known as Community Ophthalmology, now studied and practiced worldwide. She also helped bring eye surgery services to Harlem Hospital's Eye Clinic, which has since helped to treat and cure thousands of patients.

From this point on, Bath’s list of firsts continued to grow. She became the first African American resident at New York University, where she finished her medical training in 1973. Meanwhile, she also married and had a child, while completing a fellowship in 1974 in corneal and keratoporosthesis surgery.

Bath moved to Los Angeles that year with her daughter to join the faculty at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and the Charles R. Drew University as Assistant Professor of Surgery and Ophthalmology. In 1975, Bath became the first African American woman surgeon at the UCLA Medical Center and the first woman faculty member at the UCLA Jules Stein Eye Institute. In 1976, she co-founded the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness (AIPB), an organization that aims to “protect, preserve, and restore the gift of sight” for all persons, regardless of race, gender, age, or income level.

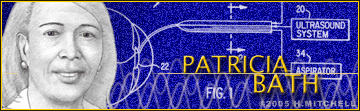

In 1981, Bath conceived of the invention for which she has become famous – the Laserphaco Probe, a surgical tool that uses a laser to vaporize cataracts via a tiny, 1-millimeter insertion into a patient’s eye. After using the Laserphaco Probe to remove a cataract, the patient’s lens can be removed and a replacement lens inserted.

Cataracts are cloudy blemishes that commonly form in people’s eye lenses, especially in men and women over the age of sixty. Eventually, cataracts can lead to blindness. Typically these have been treated with a somewhat harsh, perhaps risky, traditional surgical procedure, but Bath’s innovative device employs a faster, more accurate, and minimally invasive technique. Her idea was very advanced for its time, thus it took more than five years for her to perfect the concept and apply for a patent. She received her first patent for the device in May 1988, followed by another in December 1998. She holds four U.S. patents for innovations related to the Laserphaco, in addition to international patents from Japan, Canada, and several countries in Europe. The Laserphaco Probe has been used overseas since 2000 and has been approved for safety by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States.

In 1983, Bath was named chair of the Ophthalmology Residency Training Program, which she also co-founded, at Drew/UCLA. Bath was the first woman in the country to hold such a position. She was elected to the Hunter College Hall of Fame in 1988 and named Howard University Pioneer in Academic Medicine in 1993. Also that year, Bath retired from the UCLA Medical Center, and she became the first woman to be elected to the Center's honorary medical staff.

Bath continued to advocate telemedicine, direct the AIPB, and dedicate time to her passion—the prevention, treatment, and cure of blindness, until she passed away on May 30, 2019, due to complications from cancer. She was 76 years old.