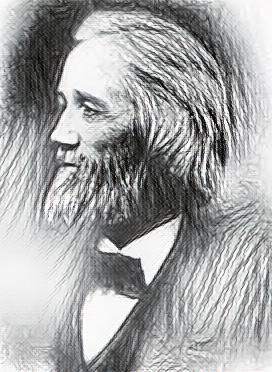

Christopher Sholes

The typewriter was reinvented dozens of times; but credit for the first practical machine is given to Christopher Latham Sholes of Milwaukee.

In 1866, Sholes and Carlos Glidden were developing a machine for numbering book pages, when they were inspired to build a machine that could print words as well as numbers. Since the 1820s, inventors had been working on personal printing machines; but Sholes, along with Glidden and their associate Samuel Soulé, resolved to build a reliable and marketable device.

A year later, they received U.S. patent #79,265 for their prototype (preserved today in a vault at the Smithsonian Institution). Although the machine lacked, among other things, a space bar and shift key, the basic elements were there. Alphabetized keys, when struck, swung little hammers (“type-bars”) with the same letters embossed in their heads that in turn struck, through an inked ribbon, a sheet of paper held against a cylindrical roller (the “platen”). Five years, dozens of trial-runs, and two patents later, Sholes and his associates produced the first practical typewriter (1872).

Its secrets were the type-bar system, and the “universal” keyboard. The type-bars were speedy but tended to catch and jam the machine; so Sholes’ business associate James Densmore suggested splitting up keys for letters used commonly together. Thus today’s standard “QWERTY” keyboard was actually invented to slow down typing.

Densmore convinced a dubious Philo Remington (whose company was best known then for its rifles) to market the device; and in 1874 the “Sholes & Glidden Type Writer” was first offered for sale. It took some years, and some further improvements from Remington’s engineers, before the machine’s sales skyrocketed. By 1908, however, it was clear that these machines would transform the business world; and they did. The typewriter was the most significant everyday business invention of the pre-computer age.