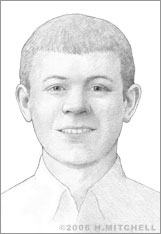

Carl Dietrich

Until recently, the concept of a “flying car” has, for the most part, been merely the stuff of dreams and movies, like “Bladerunner” and “Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.” Thanks to aerospace engineer Carl Dietrich and his team, the idea that a personal transportation vehicle could be driven like a car, and also flown like an airplane, is getting much, much closer to reality.

Born in northern California in 1978, the Sausalito native enjoyed building model airplanes with his father as a child, and by the age of eight, he knew he wanted to be an aerospace engineer one day. It was then that he began saving money to take flight lessons. He earned his pilot’s license at age 17.

Next, Dietrich entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as a major in Aeronautics and Astronautics. He earned an SB in 1999 and an SM in 2003. He continued his studies at MIT in pursuit of a doctoral degree in Aeronautics and Astronautics, which he completed in 2006.

At MIT, Dietrich made a name for himself in a variety of ways, including becoming the youngest-ever winner of the MIT Aero/Astro XVI, XVI award; winner of four undergraduate design competitions; and winner of two MIT IDEAS competition prizes, one for his design of a de-mining tool that has been tested by the United Nations. For his master’s thesis, Dietrich designed a potentially more efficient, more reliable, and less expensive rocket engine. He holds a patent for this Centrifugal Direct Injection Engine (CDIE), which operates without a turbo-pump pressurization system. He also founded the MIT Rocket Team in 1998 to develop a sub-orbital rocket.

The concept of a flying car is not exactly new, after all. Many have attempted to create such a craft since the Wright brothers completed their historic flight at Kitty Hawk, N.C., in 1913. In 1917, Glenn H. Curtiss made a short flight in his autoplane, which ultimately failed, and Felix Longobardi was awarded a patent for a vehicle capable of driving on surface roads and flying through the air in 1918. Henry Ford tried out a similar vehicle, but abandoned the project when a friend died in testing the device. A relatively successful concept was developed in the 1950s by Molt Taylor, but was never mass-produced. There have been at least 60 other published concepts, and today other companies, such as Sacramento, Calif.-based Moller Intl., are working on designs for such a vehicle as well.

Dietrich hoped that the timing, design, and efficiency of his vehicle, the Transition, will make it an historic success. The Transition is designed for consumers to use as an alternate, but not a replacement, for the family car, for trips between 100 and 500 miles. It weighs approximately 1,320 pounds, holds two adults and luggage, uses a 100 horsepower engine, and has the ability to travel 500 miles on one tank of gas. The driver can keep it in his or her garage, drive it like a car on surface roads to the nearest local airport, lower the 27-foot wings, which are folded to stick up on the sides when in "car mode," and taxi to the runway. After takeoff, the Transition can cruise at an altitude of between 3,400 and 8,000 feet with the ability to fly up to 12,000 feet. After landing, the driver-pilot can transition the vehicle back into a car and then drive it around at his or her destination.

One of the keys to the product’s success, according to Dietrich, is that the Federal Aviation Administration revised regulations on light sport aircraft in 2004, reducing the amount of training required for people seeking licenses to operate these vehicles. The Transition falls under the newly named class of Personal Air Vehicle and requires a Sport Pilot’s license to fly. Users of such a craft can take advantage of the more than 5,000 local airports in the country, many of which are currently underutilized.

In addition, the design of the Transition includes novel, automatically folding wings, can run on regular unleaded gasoline, and includes safety features such as a GPS navigation system, electronic center of gravity calculator, airbags, front and rear crumple zones, and patent-pending deformable aerodynamic bumpers. Dietrich has four patents pending on technology related to the Transition. With fellow MIT graduates Anna Mracek and Samuel Schweighart, he founded Terrafugia, Latin for “escape from land,” in 2004 to develop the product and bring it to market.

Terrafugia’s next project is the TF-X, a more convenient way to travel by flying car, as it takes off and lands without a runway—much like a helicopter. The TF-X is expected to be completed in 8 to 10 years.

The design for the Transition won MIT’s $1k competition for the consumer products division in 2005, and in 2006, Dietrich was named recipient of the prestigious $30,000 Lemelson-MIT Student Prize for the Transition and for his body of work as an MIT student. He graduated MIT that year with his PhD.

MIT recognized Dietrich as one of their sixteen exceptional graduates under the age of 35. He was also named as one of the Boston Business Journal’s “40 Under 40” in 2009.

In 2017, Dietrich sold his company to a chinese industrialist named Chao Jing. Although Dietrich sold his company, his love and passion for aeronautics and astronautics has not waned. In 2019, Dietrich started a new company called Jump Aero Incorporation. The company's goal is to facilitate eVTOL (electric vertical takeoff and landing) for first responders to help save lives.